I never used to think much about preserving the Winter fruits. The past two Winters, I indulged myself in marmalade, and I have preserved lemons in the past, but really I have yet to branch out into canned clementines, or other lightly sweetened sectioned fruit. Next Winter, I will be better prepared with a list of citrusy canning projects, but until then I'll have an orange liqueur to keep me company.

I came about "liqueurizing" an orangy concoction somewhat by accident this year. It seemed there was a buzz surrounding Cara Cara oranges, which I had never before tried, and were available at my co-op. When I ate one, they quickly became a favorite, melding a slightly grapefruit undertone with the recognizable orange. Julia had been busy making triple sec, using brandy. I was daydreaming of Spring and rhubarb season, and remembered that I hadn't tasted my rhubarb liqueur in a very long time. When I poured a little cordial glass, it was as fine and mellow as a cordial could be, all the harsh bite of gut-rot grain alcohol successfully tamed as time did it's thing.

Deena's recipe was such a good base ratio (and it stands as one of my favorite food blog posts ever), so I decided to apply the same method to oranges, hoping to create an orange liqueur that could stand in both drink and baked good as proud and bracing fresh orange substitute. When I decided to bottle it up yesterday, I feel I've succeeded, but I won't truly know until time works it's magic, and smooths out all the edges.

Deena's recipe was such a good base ratio (and it stands as one of my favorite food blog posts ever), so I decided to apply the same method to oranges, hoping to create an orange liqueur that could stand in both drink and baked good as proud and bracing fresh orange substitute. When I decided to bottle it up yesterday, I feel I've succeeded, but I won't truly know until time works it's magic, and smooths out all the edges.

iPhone pics.

Not being a huge drinker, and being downright snobbish in demanding the finest when in the company of alcohols, I consider Cointreau the gold standard, the King of orange liqueurs. I should preface that I have not ventured far down this orange paved road, triple secs in general not something I buy or drink often at all. In my mind, there are two premium options for orange liqueurs widely available, my favorite, Cointreau, and the slightly sweeter Grand Marnier. The ethereal and pearly clear sophisticate of Cointreau is a mysterious thing. It is so intensely orangy, my limited drinking self has never found anything to compare.

The bottle, at home in my spice cupboard, has flavored rice puddings and nut-studded quick breads with ease, and a splash here and there has enlivened beverages with bright, unmistakeable orange flavor. Could I dare come close to making something this incomparable?

I figured since I was near the bottom of my Cointreau bottle (I've since polished it off, adding the remainders to a rhubarb sauce for the Easter ricotta cheesecake), I could spend the money on another - or take the risk of spending about the same amount on a bottle of grain alcohol and try infusing my own.

Grain alcohol, by the way, is creepy stuff. Not only do I feel the overwhelming compulsion to explain to the clerk what I'm planning to do with the stuff, it comes with flammable warnings, and disclaimers in bold face on the very visible front of the bottle: "NOT INTENDED FOR CONSUMPTION UNLESS MIXED WITH NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE". If you ever needed a reason Not to drink something, this is probably the bottle for you. It does, however, do a stellar job of leaching every last drop of color and flavor from whatever you drop into it, making it the perfect medium for liqueur base.

Grain alcohol, by the way, is creepy stuff. Not only do I feel the overwhelming compulsion to explain to the clerk what I'm planning to do with the stuff, it comes with flammable warnings, and disclaimers in bold face on the very visible front of the bottle: "NOT INTENDED FOR CONSUMPTION UNLESS MIXED WITH NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE". If you ever needed a reason Not to drink something, this is probably the bottle for you. It does, however, do a stellar job of leaching every last drop of color and flavor from whatever you drop into it, making it the perfect medium for liqueur base.

Partially inspired by Marisa's post on dehydrating lemons and limes, and my "internet friend" E. from Maine, I sliced 4 Cara Cara oranges thinly and dehydrated them until crisp. I added them to the peel of 6 or 8 (I can't quite remember) navel oranges in a half gallon canning jar. Then, I poured in the grain alcohol, screwed the top on tight, and forgot about it for a month as it sat on the shelf in my dark basement. The shocking traffic cone orange and the pure orange scent was overwhelming, and both were cues that I should bottle.

Using Deena's formula and the trusty Metric System, I used a beginning measure of infused grain alcohol (866 mL), added 1 1/2 times spring water (1299 mL) and the bare bones of sweetening: half of the beginning measure of sugar (433mL). (Yes, I know I should not have probably used mL's to measure the sugar, but I did.) I heated the water/sugar just enough to dissolve all of the sugar, and then let it cool. When I added it to the crystal orange clarity of the base alcohol, I was surprised as it turned opaque. When I tasted it, it was a little harsh, a little sweet, and a little bitter, but it was also fully orangy and already quite good.

Using Deena's formula and the trusty Metric System, I used a beginning measure of infused grain alcohol (866 mL), added 1 1/2 times spring water (1299 mL) and the bare bones of sweetening: half of the beginning measure of sugar (433mL). (Yes, I know I should not have probably used mL's to measure the sugar, but I did.) I heated the water/sugar just enough to dissolve all of the sugar, and then let it cool. When I added it to the crystal orange clarity of the base alcohol, I was surprised as it turned opaque. When I tasted it, it was a little harsh, a little sweet, and a little bitter, but it was also fully orangy and already quite good.

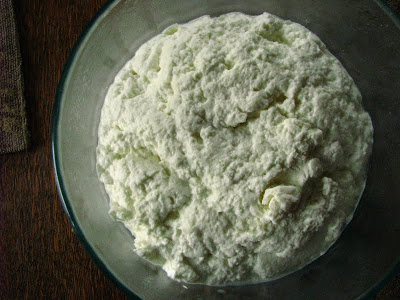

It seemed like the Cara Cara oranges "rehydrated", but they were brittle and dried when removed from the grain alcohol.

a blurry comparison of color pre-dilution (left) and post-dilution (right).

Will I give up Cointreau and it's gorgeous opalescence in sole favor of my new homemade version? Not likely. But I feel that mine will be at home in baked goods, jams and glazed carrots to be sure. The tangerine opaqueness is a pretty thing to look at sitting on my counter, but I know I must soon transfer it to the dark basement to both preserve it's color and let it mellow.

I saved last year's boozy rhubarb remains and cooked them down. Too strong to be eaten on it's own, it did make a good kombucha flavorant... but I don't think the brittle, alcohol-dried orange peels will do the same. They are still sitting in a bowl on my counter, since it pains me to have to throw them out. Just a nibble on them makes my tongue numb from both the bitter peel and the creepy-strong grain alcohol. Any suggestions before the whole lot goes into the garbage? Not sure about composting it, what with the high toxicity of that alcohol...

I saved last year's boozy rhubarb remains and cooked them down. Too strong to be eaten on it's own, it did make a good kombucha flavorant... but I don't think the brittle, alcohol-dried orange peels will do the same. They are still sitting in a bowl on my counter, since it pains me to have to throw them out. Just a nibble on them makes my tongue numb from both the bitter peel and the creepy-strong grain alcohol. Any suggestions before the whole lot goes into the garbage? Not sure about composting it, what with the high toxicity of that alcohol...

color leached oranges.

Our Spring is very fickle this year. It's cold, rainy, cloudy and then there will be an 80 degree day directly followed by a 45 degree one. Maybe that is why the sunny orange of this liqueur appeals to me so much. Maybe that is why citrus seems so great in the Winter. No matter the season, citrus preserved is something that never fails to make me happy. For no other reason than the surreal color, I am glad for my experiments with this orange liqueur.