May’s Daring Bakers’ Challenge was pretty twisted – Ruth from

The Crafts of Mommyhood challenged us to make

challah! Using recipes from all over, and tips from “

A Taste of Challah,” by Tamar Ansh, she encouraged us to bake beautifully braided breads.

I have never made

challah before, but was thrilled at the idea of making it for the challenge this month. Generally, I prefer the "lean" breads to enriched ones, rarely making fortified loaves that include butter, sugar and eggs. Sourdough has thoroughly taken over my life, wild yeast ruling almost all of my bread baking experiments. I nearly let sourdough play a role in this bread, but after considering Nancy

Silverton's recipe, I thought better of it after her description of the interior was "ropey". I didn't want ropey bread. I wanted soft-as-a-pillow, tender bread, one that reminded me of the

Pan de Muerto from last November.

Bread that was a full dessert in a slice.

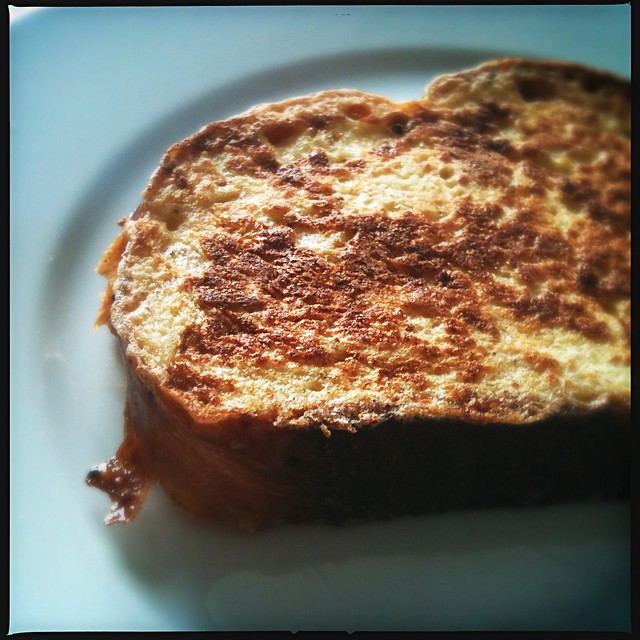

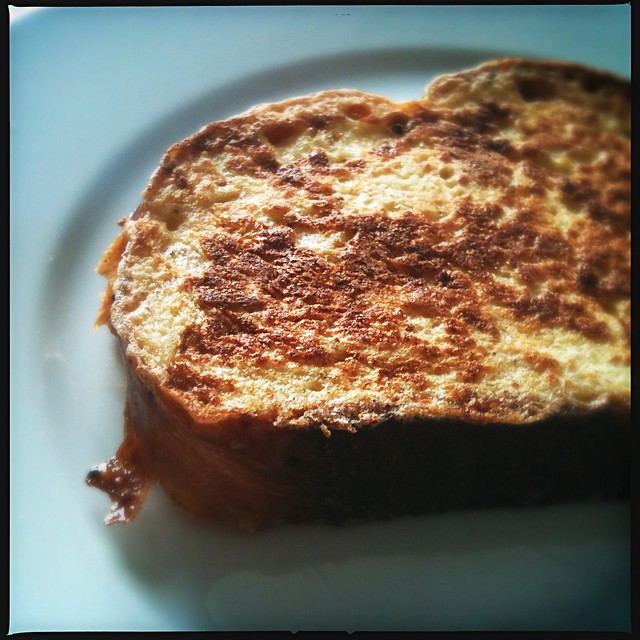

This bread is not as fortified as Pan de Muerto, and much lighter than brioche (which I haven't made either - what am I waiting for?) This bread is beautifully soft and close-crumbed, just barely sweet and could easily be swayed in either direction for a sweet or savory application. Just baked and fresh, it is light and almost airy, and it makes the most wonderful toast as it stales gracefully.

Fortified breads always stale more quickly than lean ones, but when good toast is at play I couldn't be more happy. This bread toasts to a golden brown, and the innards seem to be refreshed by the toaster. It's delicately crunchy, and the burnished crust surprisingly doesn't get any darker. It's really a loaf of bread I would even make exclusively for toast. And that is saying something.

I decided to use Peter

Reinhart's recipe for

challah from

Crust and Crumb. Even though I have had this book for a whole year now, I am still just as excited about it. Every time I crack it open, I find inspiration and good storytelling - and even though I have read it cover to cover, I still feel like I'm learning new things. It is one of my favorite books, and one that I know will continue to prove itself over and over.

The only thing I found that differed in the recipe was the baking time. My loaf was fully baked at just over 25 minutes. I confirmed the internal temperature to be certain I wouldn't have a doughy middle when I cut into it; after it cooled, I cut into it and it was just perfect. Deep dark exterior and creamy yellow crumb, I worried that my mahogany crust would taste burnt, but it did not at all.

I made this loaf entirely by hand. Since the demise of my stand mixer, I approach all bakery projects a little differently. As I made this one, I thought of my Amish friends just down the road from my Parents. When I last visited, Lizzy had showed off her retro-fitted stand mixer - one that had no electricity, but was converted to a hand crank that worked on the principle of leverage. It was a genius design really, that allowed for faster mixing as the handle was moved in towards the center of the crank. I'm not sure how that man-powered machine would do with kneading breads, but I have to say that I am half considering that type of model if/when I replace mine.

While a highly fortified (and sticky) dough like the Pan de Muerto could not be made without a stand mixer, this one did just fine. It was a bit of a workout, but the dough was so silky and soft in spite of the little stickiness that it was a pleasure to work with. I just kneaded until a bit of the dough passed the windowpane test, about 15 minutes or so, using additional flour as sparingly as possible.

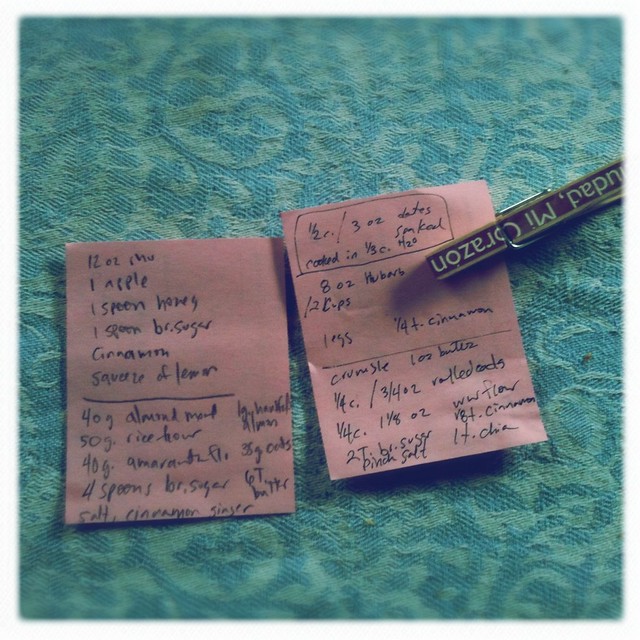

(Peter

Reinhart, Crust and Crumb)

makes 1 loaf

- 16 oz. ( 3 1/2 c.) bread flour

- 2 oz. (1/4 c. sugar)

- 1 t. salt

- 2 t. instant yeast

- 1 oz. (2 T.) unsalted butter, softened

- 2 large eggs

- 2 large egg yolks

- 1 egg yolk for egg wash

- 2 oz. (1/4 c.) milk, room temperature

- 4 oz. (1/2 c.) water, room temperature

- poppy seeds (or sesame seeds) for topping, optional

Combine all ingredients in a mixing bowl except the egg wash egg yolk and seeds for topping. Stir until it forms a ball, then turn it out onto lightly flour counter and knead 12-15 minutes until the dough is "soft, pliable, and neutral to the touch". It should be slightly tacky and pass the windowpane test. (Reinhart says that if using a stand mixer, this will take about 10 minutes.)

Place the dough in a clean bowl, cover tightly with plastic wrap, and let rise for about 1 hour until it swells noticeably. Then, remove the dough from the bowl, and knead by hand for 5 minutes. Return to the bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and let rise a second time for another hour. It will swell noticeably a second time.

Divide the dough into 3, 4, 5, or 6 (or 12 to represent the 12 tribes of Israel) strands for braiding. (I weighed my dough, then divided by 4, since I did a 4 strand braid.) Round the pieces into balls, and cover with oiled plastic wrap. Let them rest for 20 minutes.

Working quickly "to minimize handling of the dough", roll each piece into a long snake that is fatter in the middle and tapered at the ends. Reinhart says to make the ropes about 8 inches long, but mine were longer, about 12 inches. (The loaf will be longer and thinner if you do it my way, and shorter and plumper if you stick closer to the 8 inches.) Secure the ends together and braid - there is a good video here illustrating the 4-strand braid that I did. Transfer the loaf to a parchment lined baking sheet.

Whisk the egg yolk for egg wash, and brush the loaf with the beaten yolk. Re-cover with the oiled plastic wrap, and let rise until doubled in size, about 1 hour. Reserve the egg yolk for a second brushing. (I actually brushed with the egg yolk, sprinkled with the poppy seeds and then let it rise. I omitted the next step of brushing with egg yolk a second time.)

Towards the end of the final rise, preheat oven to 375 with the rack in the center. Just prior to baking, brush again with the egg yolk and sprinkle with poppy or sesame seeds if using. Bake for 45 minutes (mine took just less than 30) until deep golden and the internal temperature registers at least 185 degrees in the center.

Let cool at least 45 minutes before slicing.

My bread may have baked in less time because it was longer and thinner, and perhaps it was darker because I didn't brush it with the egg yolk a second time just before baking it? At any rate, it was a great loaf of bread. I shared half with some friends, and baked some into French toast the next morning. It was the finest French toast that I ever made!

I have long been fascinated with Jewish food traditions although I am not Jewish myself, so I really enjoyed the challenge this month, and the opportunity to learn a little more about the Jewish customs surrounding challah. Challah is traditionally made weekly, a duo of loaves made as well as you can make them to commemorate the holiness of the Sabbath and represent the double portion of manna provided to the Israelites so they could observe the commandment of not working on the Sabbath. I read in several different sources about the symbolism of challah, how the braids and white flour have special meaning, how a portion of the dough was presented as an offering, and and how when presented at the table the loaves can be covered with a decorative cloth to represent the dew that covered and preserved the manna. But, I particularly enjoyed this paragraph from Peter Reinhart which makes challah-making as important to a Christian baker as a Jewish one:

Challah, like bagels, has evolved from its Jewish roots into a mainstream bread enjoyed by people of all backgrounds. When made properly, it is a stunningly appealing loaf, plump and shiny, its braided strands symbolizing the interweaving of heaven and earth, God and mankind. Whether or not we read deeply into the symbolism of challah, we face the same challenge as with all breads: how to make an excellent loaf.

I look forward to making more challah, perhaps some loaves that are more plump and more intricately woven. Meanwhile, I will check the

Daring Baker blogroll for more inspiring loaves! Be sure to also check out

the recipes on the Daring Kitchen website, there is a range of richness stemming in the amounts of butter used.

This post has also been

Yeastspotted.